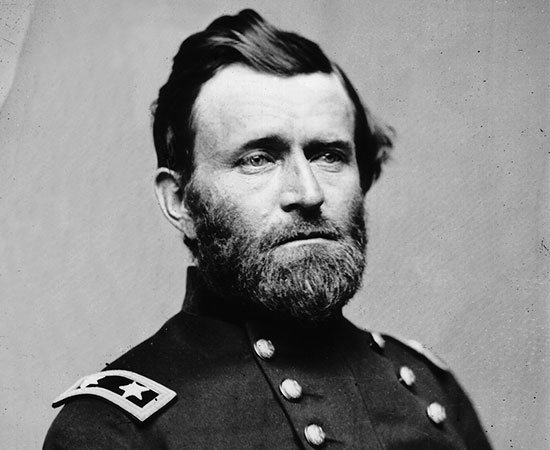

1. Find a Profession Where Your Passion Meets Your Purpose. The same man who decisively and strategically lead over a million soldiers through a brutal Civil War, was unable to manage his brother’s leather goods store in Galena, IL in civilian life. Context matters. Grant was not just twice as successful or three times as successful as a military leader compared to a business leader, he was a thousand times more successful. Finding the profession most suitable to your talents and most aligned with your purpose might be the biggest factor impacting your success as a leader. It was for Grant.

2. Although Your Strengths Can Take You Far, Your Biggest Weakness Can Derail Your Career and Your Life. Grant was a natural leader with the temperament, intellect and disposition to lead men into battle. However, despite these towering strengths, he had one weakness that constantly threatened to ruin his career – alcohol. People didn’t understand alcoholism back then. Alcohol abuse was attributed mainly to insufficient will power. Grant was able to mitigate this weakness namely through the help of his wife, Julia, and his good friend John Rawlins. He surrounded himself with people who understood his weakness, and vigilantly protected him by ensuring he was rarely in situations that would be tempting.

3. Decisiveness. Grant understood that making a wrong decision was bad, but often delaying the decision altogether was much worse. “In war anything is better than indecision,” Grant said. “If I am wrong we shall soon find out, and can do the other thing, but not to decide wastes both time and money and may ruin everything.”

4. Coolness under Pressure. When the heat of battle was on, Grant could remain calm and his thinking remained lucid. Lincoln was frustrated by most of the Union Generals, but not Grant. Lincoln commented: “The great thing about Grant is his perfect coolness and consistency of purpose…he is not easily excited and he has the grit of a bulldog.”

In his memoirs Grant tells the story of the first time he personally led his regiment into combat. His mission was to capture the Confederate General Thomas A. Harris who commanded twelve hundred men. There was rising tension as Grant and his men approached a small hill where they suspected Harris and his army awaited them in the creek bed on the other side. Grant’s biographer Ron Chernow describes the scene:

Grant described his first whiff of fright as his heart “kept getting higher and higher until it felt to me as though it was in my throat. I would have given anything then to have been back in Illinois, but I had not the moral courage to halt.” To his relieved astonishment, Grant discovered that Harris and his men had absconded in response to his approach. “My heart resumed its place. It occurred to me at once that Harris had been as much afraid of me as I had been of him.” This anticlimactic moment was formative for Grant, who never forgot the nugget of practical wisdom learned. He would emerge as a master of the psychology of war, intuitive about enemy weakness. Henceforth he would project himself into opponents’ minds and comprehend their fears and anxieties instead of blowing them up into all-powerful bugaboos, giving him courage when others quailed.

5. Focus on What You Can Control. In the early years of the Civil War, General Lee scored a string of Confederate victories and he took on a mystique of invulnerability. Grant was always railing against this tendency. When discussing Lee with his men he said, “some of you always seem to think he is suddenly going to turn a double somersault and land on our rear and both of our flanks at the same time. Go back to your command and try to think what we are going to do ourselves, instead of what Lee is going to do.” He wanted to eliminate the defeatist mentality that had seeped into his officers, and get them thinking confidently about winning the war.

6. Never Blame Others. If there was a mistake or things didn’t go well, Grant always took responsibility. In a famous dispatch to Lincoln during the war he wrote; “Should my success be less than I desire…the least I can say is, the fault is not with you.” This is a far cry from the previous Union Generals who were always complaining to Lincoln they didn’t have enough troops or supplies, and every defeat was attributed to some problem or scapegoat in Washington.

7. Integrity. Grant was raised in an abolitionist family. He always believed that slavery was a moral evil. At times, this belief was challenged, yet he always chose the more virtuous path. After being discharged from the Army, Grant was living in what many would consider poverty and was struggling to provide for his family. Because his wife came from a slave-holding family, his father-in-law gifted him a slave, presumably to help him provide for his family. Although Grant could have raised a considerable sum of money if he had sold the slave, he promptly freed him. He never placed money or fame above his own integrity.

During the Civil War, even many Northern soldiers and officers, although they were against slavery, harbored racists views. Grant always maintained the equality and dignity of black Americans. Early in the war he envisioned a pathway from slavery to citizenship. He placed John Eaton in charge of developing a policy toward the many freed slaves who were flocking to Grant’s Army. Grant wrote to Eaton a lengthy list of contributions blacks could make toward the Union Army, including building bridges, chopping wood, and working in the kitchens and hospitals. Eaton said this about Grant:

“He went on to say that when it had been made clear that the Negro, as an independent laborer…could do these things well, it would be very useful to put a musket in his hands and make a soldier of him, and if he fought well, eventually put the ballot in his hand and make a citizen of him. Obviously, I was dealing with no incompetent, but a man capable of handling large issues. Never before in those early and bewildering days had I heard the problem of the future of the Negro attacked so vigorously and with such humanity combined with practical good sense.”

8. Strategic Thinking. Grant could look beyond the current battle or campaign, and devise a strategy to win a decisive victory in an entire theater of war. To do this he had to project into the mind of his adversary and predict how they were going to react. He also understood the value of logistics and supplies. Grant would often gain the advantage by cleverly sustaining and supplying his Army as it moved quickly across varied terrain to gain an upper hand. These movements would surprise the enemy and put them in a compromising position. Grant’s biographer Ron Chernow:

Before Grant became chief general, the Union’s military effort had been fragmented and disjointed, deprived of a single supervisory mind to govern the whole enterprise. “Eastern and Western armies were fighting independent battles, working together like a balky team where no two ever pull together,” Grant recalled. Now he mapped out an overarching design that encompassed all Union Armies.

9. Give Credit Away. During the Civil War, Grant found himself dug in at a position, and he was resolved to stand his ground and not retreat. While composing a dispatch to President Lincoln, he wrote: “I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes me all summer.” Then in a simple yet bold move he struck the word “me” from the message, and completely transformed it from a personal note to a powerful rallying cry. After all, he wasn’t holding the line by himself. Grant understood that it was his men, the entire Army of the Potomac that was working together to hold their position. The line “I propose to fight it out on this line if takes all summer” has a completely different feel, and it not only rallied the troops, but it also caught the imagination of the public. It became one of his most famous lines from the Civil War.

At another point in the war, when Grant was lauded for his success, he attempted to deflect attention and give credit to his commanding officers. Addressing General Sherman, Grant said “whilst I have been eminently successful in this war…what I want is to express my thanks to you and McPherson as the men to whom, above all others, I feel indebted for whatever I have had of success.”

10. Magnanimity in Victory. As the Civil War was reaching its inevitable finality, Grant was worried that a humiliated South would retreat to Guerilla warfare, and the eventual reunification of North and South would take much longer than necessary. So, in a gesture of goodwill, Grant did not ask for draconian terms of surrender that may have humiliated General Lee and his officers. Instead he was gracious and offered Confederate Soldiers the right to return home to care for their families, and officers were allowed to keep their side arms and horses. When Grant asked Lee if the terms were satisfactory, Lee said “Yes, I am bound to be satisfied with anything you offer. It is more than I expected.” Lee went on to say, ” This will have the best possible effect upon the men. It will be gratifying and will do much toward conciliating our people.”

A lesser leader might have given in to the personal need to exact vengeance and humiliate his enemy – Grant was above all that. Having endured humiliation through the failure of his civilian life, he understood the power of offering help when one needs it the most. Grant’s act of generosity was also part of his strategic thinking. He was already looking beyond the war, and making decisions that were in the best interest of the future of his country.

11. Don’t Hide Behind Uniforms or Titles, Just Be Yourself. Grant was not some protected General who never interacted with his men. And he never relied on his rank or uniform to command the respect of others. He earned respect through his leadership, and his willingness to walk among his soldiers, talk with them and listen. Chernow relates the following story:

Grant never assumed military airs and talked casually with his men, as if he were a peer. “He sat on the ground and talked with the boys with less reserve than many a little puppy of a lieutenant, ” wrote an Illinois soldier. Everyone notices Grant’s strangely nonchalant demeanor in a war zone. One day he strolled about in full view of Confederate marksmen as enemy bullets raised the dust around him. A newspaper reporter who did not recognize him shouted; “Stoop down, down, damn you!” Grant did not flinch.

At Appomattox Courthouse, where Lee surrendered to Grant, Lee was wearing a shiny new uniform with accompanying sword and polished boots while Grant famously showed up in well-worn uniform, tattered gloves and muddy boots. For Grant, it wasn’t the uniform that made the general. His leadership was based entirely on his character, values and formidable skills.

12. Listen to Others and Be Respectful. Grant was a master listener and communicator. He would take the time to listen to his staff officers and soldiers. And when he wasn’t listening he would tell stories using humor. One of Grant’s officers, Ely Parker, made the following observation:

“General Grant had a wonderful power of drawing information from others in conversation without being aware that they were imparting it. His memory of facts was good, and for faces remarkable. He recognized people after a period of twenty years and recalled their names immediately. He always would speak of the good in a man rather than the evil, and if he had to speak of the bad qualities in a man, he would close his remarks with the mention of his good points, or excuses why he did not have them.”

If you’re interested in learning about Grant and the Civil War, I highly recommend Grant by Ron Chernow.

Sean P. Murray is an author, speaker and consultant in the areas of leadership development and talent management. Learn more at RealTime Performance.

Follow Me on Twitter: @seanpmurray111

Join my mailing list and be updated when I publish new articles.

Terrific! Well put. Nuggets for all future leaders.