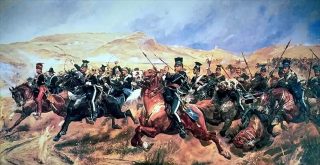

Battle of Bosworth, as depicted by Philip James de Loutherbourg (1740–1812)

On August 22, 1485, King Richard III led his troops into the Battle of Bosworth Field in Leicestershire, England. Things didn’t go well for Richard III that day. In the heat of battle, he found himself unhorsed and in desperate need of help. Shakespeare immortalized the moment with the famous line; “A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse!”

A horse was not forthcoming and Richard III was eventually slain on the battlefield. It was his last day on earth and the last day of his reign. In fact, there were a lot of “lasts” that day. Richard was the last king of the House of York and the last king of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat at Bosworth field was the last battle of the War of the Roses, and his death marks, for many historians, the end of the Middle Ages.

But something much more momentous ended that day. Richard III was the last English king to die during battle.

Richard III had his flaws, but he also had something that seems to be missing from so many modern-day leaders; skin in the game. Richard III did not ask or coerce other people to fight his battles for him. He summoned the courage to personally lead his soldiers in battle. He shared the upside, but he also shared the downside. There was symmetry in both the risk and the rewards.

Nassim Taleb explores this concept in his book Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life. According to Taleb, Skin in the Game is a powerful force that is critical for complex societies and cultures to flourish:

“It’s not just that skin in the game is necessary for fairness, commercial efficiency, and risk management: skin in the game is necessary to understand the world.”

In the 500 years since Richard III’s death, a new kind of leader has wiggled its way to the top of many of our institutions. These leaders have no skin in the game. They keep the upside while transferring the downside to others. Consider the symmetry of risk and reward for Richard III compared to the asymmetry apparent in the Royal Family of England today. Prince Harry certainly benefits from being a Royal, yet in 2008 while serving a tour of duty in Afghanistan he was summarily recalled to England “for his own safety.” However, it’s not just Royals. Taleb calls out certain professions as being the worst offenders; bureaucrats, politicians, bankers, large corporations with close ties to the government and centralized government itself.

Applying the “Skin in the game” test is a great way to filter information and people. Taleb eloquently describes this as “Bullshit Detecting: You can’t separate knowledge or anything from contact with the ground.”

Antaneus and the Importance of Being Grounded

Taleb tells the story of Antaneus, the semi-giant and son of Mother Earth from Greek mythology. Antaneus had a habit of forcing passersby to wrestle. Given his incredible strength, he inevitably pinned them to the ground and crushed them. Antaneus was considered invincible, except for one weakness: he derived his power from contact with Earth. As long as his feet were planted firmly on the ground, he could not be beat. Along comes Hercules with a plan to exploit the weakness. He picked Antaneus off the ground rendering him powerless. Deprived of contact with his Mother Earth, Antaneus was quickly defeated. The moral of the story is, of course, to “stay grounded.”

What lesson does this hold for our modern world? Beware of people (pundits, policy wonks, certain types of journalists and academics) who operate purely in the world of theory or academia. They are lacking a critical feedback loop. If you are insulated from the impact of your mistakes, you fail to learn:

“Contact with the real world is done via skin in the game ¬– having an exposure to the real world and paying a price for its consequences, good or bad. The abrasions of your skin guide your learning and discovery.”

Pain, abrasions, blood – these are caused by contact with the real world. When we make bad decisions our bodies tell us about it and we learn. The Greeks called this pathemata mathemata, or “guide your learning through pain.” Those without skin in the game don’t feel the pain of their mistakes and thus fail to learn and improve with time:

“Skin in the game means you own your own risk. It means people who make decisions in any walk of life should never be insulated from the consequences of those decisions, period. If you’re a helicopter repairman, you should be a helicopter rider. If you decide to invade Iraq, the people who vote for it should have children in the military. And if you’re making economic decisions, you should bear the cost if you’re wrong.”

Highly centralized systems pose a problem. They are filled with bureaucrats who are insulated from the consequences of their decisions. They don’t have skin in the game. To remedy this, Taleb recommends decentralization or what he prefers to call localization, so there are fewer decision makers immune from their actions. Decentralization removes large structural asymmetries.

Warren Buffett and Berkshire

Skin in the game is a trait Warren Buffett seeks to establish in Berkshire and the companies he invests in. For example, he looks for companies where management owns large blocks of shares, so their interests are aligned with ownership. He also looks for Boards with Directors who own significant shares. But it’s not enough that managers and directors own large stakes, they have to purchase those shares with their own money in the open market. Stock grants and options, so common in tech companies, don’t count. A stock option is really the shareholders skin in your game. That share has to come from somewhere, and it effectively comes by diluting the other shareholders.

Berkshire itself is also a model of skin-in-the-game optimization. Buffett prefers a streamlined organization structure, with minimal bureaucracy. Unlike conglomerates like GE, Berkshire has only 25 people at headquarters. There is no centralized layer of management making decisions for operating companies while insulated from the impact of those decisions.

People with skin in the game make better decisions over the long-term. Leaders with skin in the game are better leaders. And organizations structured to optimize for skin in the game are more robust, and more likely to survive.

About the Author

Sean P. Murray is an author, speaker and consultant in the areas of leadership development and talent management. Learn more at RealTime Performance.

Follow Me on Twitter: @seanpmurray111

Join my mailing list and be updated when I publish new articles.