Winston Churchill (1874-1965) was a soldier, writer and statesman who led England and the Allies to victory over Nazi Germany in World War II. His life spanned from the Victorian Age to the Space Age. He authored 37 books, producing more words than Shakespeare and Dickens combined. When Western Civilization was threatened by the ominous expansion of totalitarianism, Churchill defended liberty against tyranny, exuded a confidence in victory and provided something freedom-loving people across Europe and the United States desperately needed: hope.

1. Think for Yourself

Churchill was an independent thinker. He had the courage to hold views that were unpopular. During the 1930s, when Churchill was out of power, he recognized the threat posed by Nazi Germany and called for British rearmament. World War I was billed as the “War to end all wars,” so the conventional view was that Europe had entered an extended period of peace. It was a compelling idea, and the people and politicians of that era very much wanted for it to be true. However, Churchill saw Hitler for who he was, and as he watched Germany invest heavily in its military, Churchill called for Britain to do the same. He was vilified in the press, other politicians called him a warmonger and the people said he was out of touch. The prime minister at that time, Neville Chamberlain, adopted a policy of appeasement toward Germany, and it was popular with the people of England. Appeasement culminated in the Munich Agreement, whereby Nazi Germany was allowed to occupy and annex the Sudetenland and essentially all of Czechoslovakia. Chamberlain famously claimed he had secured “Peace in our time.” Churchill gave a speech in the House of Commons with a different view:

“I will therefore begin by saying the most unpopular and unwelcome thing. I will begin by saying what everyone would like to ignore or forget but which must nevertheless be stated, namely that we have sustained a total and unmitigated defeat.”

– Winston Churchill, Address to House of Commons, October 5, 1938

2. Self-Education

Churchill attended Harrow, a prestigious boarding school where he was an average student. Many of his classmates went on to obtain a classical education at Cambridge or Oxford. Churchill took a different path and attended Sandhurst, the British military academy, where he learned military strategy, tactics and horseback riding. Upon graduation he was stationed in India and found himself with ample free time. Rather than waste this time in frivolous pursuits, as many of his fellow officers did, he dedicated himself to reading the classics. He started with Edward Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, a 4,000 page volume. Next he read Gibbon’s autobiography and Macaulay’s six volume History of England. Over a two year period he worked his way through the great books of Western Civilization including Plato, Aristotle, Schopenhauer, Darwin, Adam Smith and many more. His ambitious reading program sparked his life-long curiosity and love of learning, and left him with an education that rivaled those of his Harrow classmates who attended university. Churchill essentially learned how to learn, a skill he would put to use throughout his life.

3. Writing

Churchill came from an aristocratic family and grew accustomed to the good life, but his fortunes changed when his father died. Suddenly he needed to earn money to maintain his lifestyle. Here is how Churchill describes it:

“When I was twenty-two, with my small Army pay not covering expenses, I realized that I was…unable to live my life as I wanted to. I wanted learning and I wanted funds. I wanted freedom. I realized there was no freedom without funds. I had to make money to get essential independence; for only with independence can you let your own life express itself naturally. To be tied down to someone else’s routine, doing things you dislike – that is not life – not for me….So I set to work. I studied. I wrote. I lectured…I can hardly remember a day when I had nothing to do.”

– Winston Churchill

Churchill discovered he could write vivid narrative, using short words and short sentences, under tight deadlines in war zones. He mastered what he called the “Noble English sentence.” Publishers were willing to pay dearly for this skill. Early in his career Churchill became a dual war correspondent and military officer, blending the lines in many ways that would not be acceptable today, but were routine in his day. Later in life Churchill became a writer of history, including his four volume History of the English Speaking Peoples. Churchill’s skill as a writer made him a better communicator, orator and leader. The act of writing also served as a means of reflection. His command of history allowed him to draw parallels to the challenges he faced in his own day. He would often draw analogies and inferences from the lives of Napoleon, Marlborough, Nelson, Wellington and others. In 1953 Churchill was awarded the Noble Prize in Literature “for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values.”

4. The Power of Words

Churchill had an innate sense for the power of words and understood the emotional impact they convey. While discussing strategy with British General Harold Alexander during World War II, the general referred to the Continent as “Hitler’s European Fortress.” Churchill immediately turned on the general in anger. “Never use that term again. Never use that term again!” The last thing Churchill wanted was the image of “Hitler’s European Fortress,” leaking out to the British people and armed forces. It could only be to Hitler’s advantage to have such an image locked in people’s minds.

For Churchill, word choice mattered. He strived to be both precise and concise. In 1940 Churchill worried the German army would invade England. The Ministry of Information drafted a message telling people to “stay put,” in the event of an invasion. Churchill was critical of the term. “It does not express the fact. The people have not been ‘put’ anywhere.” He suggested ‘Stand Firm’ instead.

He preferred old, often archaic words to new words because he believed they strengthened his message. When refereeing to Germany he often used the term “foe” instead of enemy.

Churchill was a master of repetition:

“We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender…”

– Winston Churchill, Address to the House of Commons, June 4, 1940

Another example:

“You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word: victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of terror, victory however long and hard the road may be; for without victory there is no survival.”

– Winston Churchill

At one point during the Blitz Churchill grew tired of reading dispatches where some enemy planes were reported ‘out of action’ and others “destroyed.’ “Is there any real difference between the two or is it simply to avoid tautology?” A close friend of Churchill observed this about him; “Nothing irritated him more than over-complication of issues or the use of obscure language by those who thought they were being clever by making themselves incomprehensible to ordinary people.” (Churchill, Walking with Destiny by Andrew Roberts p. 610)

5. Moral Clarity

More than any other leader in the twentieth century, Churchill articulated the moral case for defending Western values. He stood up for the freedom of the individual against tyranny. Toward the end of World War II he could safely predict that the Allies would win, but he nevertheless reflected on how perilous the situation was, and how high the stakes were, not just for his generation, but many generations into the future:

“We shall reach the end of our journey in good order, and the tragedy which threatened the whole world and might have put out all its lights and left our children and descendants in darkness and bondage – perhaps for centuries – that tragedy will not come to pass.”

– Winston Churchill

He also recognized that he came from a privileged background and he could see past the War toward a society that offered more equitable opportunities:

“When the war is won by this nation, as it surly will be, it must be one of our aims to work to establish a state of society where the advantages and privileges which hitherto have been enjoyed only by the few shall be far more widely shared by the many and the youth of the nation as a whole.”

– Winston Churchill

And he understand that everyone is engaged in a moral struggle that will eventually define their life

“The only guide to a man is his conscience; the only shield to his memory is the rectitude and sincerity of his actions. It is very imprudent to walk through life without this shield, because we are so often mocked by the failure of our hopes and the upsetting of our calculations: but with this shield, however the fates may play, we march always in the ranks of honor.”

– Winston Churchill

Church ultimately understood that as we encounter the twists and turns of life, there are some principles and ideas that demand the ultimate sacrifice:

“You must look very deep into the heart of man, and then you will not find the answer unless you look with the eye of the spirit. Then it is that you learn that human beings are not dominated by material things, but by the ideas for which they are willing to give their lives or their life’s work.”

– Winston Churchill

6. Personal Courage

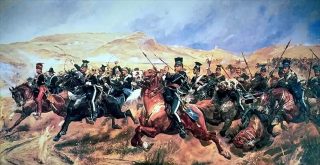

In September 1898, at the age of 23, Churchill took part in the last great Cavalry charge in British history at the Battle of Omdurman. Out-numbered ten to one, Churchill led his regiment into a swarm of enemy soldiers. Here is how Churchill describes is:

“I found myself surrounded by what seemed to be dozens of men. Straight before me a man threw himself on the ground…I saw the gleam of his curved sword as he drew it back for a ham-stringing cut. I Had room and time enough to turn my pony out of his reach and leaning over the offiside, fired two shots into him at about three yards. As I straightened myself in the saddle, I saw before me another figure with uplifted sword. I raised my pistol and fired. So close were we that the pistol itself actually struck him. Man and sword disappeared below and behind me.”

– Winston Churchill

A year later, during the Boer war in South Africa, Churchill was on a military reconnaissance train traveling through enemy territory. In a guerilla move, the Boers placed rocks on the tracks and derailed Churchill’s train. Sharpshooters waiting in ambush took aim at the survivors of the wreckage. Churchill, relatively unharmed, took command of the situation. He walked among the survivors, while bullets whizzed by his head, saying “keep cool, men.” Here is how Churchill’s biographer, Andrew Roberts, described the situation:

“Churchill displayed great bravery and initiative in leading some survivors on to the track and then spending half an hour heaving the two overturned trucks off the line so that the badly damaged engine with fifty survivors could escape….most of them wounded, while he stayed to rally the rest of the trapped and outnumbered troops. In all he spent about ninety minutes under almost continuous fire.”

– Andrew Roberts on Churchill

Later, during the German bombing of London known as the Blitz, he famously would run toward those areas being bombed, not away from them, much to the consternation of those charged with keeping him safe. He understood the importance of having skin-in-the-game. When his advisors wanted to move his residence and cabinet out of London during the Blitz, he refused, insisting that he take on same risk he was asking his people to accept.

Churchill displayed courage in other ways as well. For example, when it came time to dismiss a General or Minister in the Government, he would move quickly and decisively even if that person was a close personal friend, as they often were. At one point during World War II, Churchill sacked his good friend, Admiral Roger Keyes, by writing to him:

“I have to consider my first duty to the State, which ranks above personal friendship. In all circumstances I have not choice but to arrange for your relief.”

– Winston Churchill

7. Oratory

Churchill had many talents, but perhaps his greatest was his unmatched skill as an orator. His mastery of the English language combined with personal courage and independent thinking led to a potent ability to stir the hearts of the people. Churchill defended the timeless values and principles of Western freedom and democracy, while also providing hope that the Nazi menace would eventually be defeated.

In June 1940, Germany had conquered France and was preparing to invade England. It was not at all certain that England would prevail in the conflict, yet Churchill offered optimism and hope:

“I have, myself, full confidence that if all do their duty, if nothing is neglected, and if the best arrangements are made, as they are being made, we shall prove ourselves once again able to defend our island home, to ride out the storm of war, and to outlive the menace of tyranny, if necessary for years, if necessary alone…That is the will of Parliament and the nation…we shall not flag or fail.”

– Winston Churchill

And on the eve of the Blitz, Churchill delivered one of the most famous and memorable lines of the 20th century:

“Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour.’”

– Winston Churchill, Address to the House of Commons, June 18, 1940

Sources

- Churchill: Walking with Destiny, by Andrew Roberts

- Churchill’s Address to the House of Commons, June 4, 1940

- Churchill’s Address to the House of Commons June 18, 1940

Related Articles

- Benjamin Franklin: 10 Lessons on Wisdom

- Viktor Frankl: 5 Lessons from Man’s Search for Meaning

- Ulysses S. Grant: 12 Leadership Lessons

- Lewis & Clark: 5 Leadership Lessons

- Google: 8 Most Important Qualities of Leadership

- Phil Knight: 7 Leadership Lessons from Nike

About the Author

Sean P. Murray is an author, speaker and consultant in the areas of leadership development and talent management. Learn more at RealTime Performance.

Follow Me on Twitter: @seanpmurray111

Join my mailing list and be updated when I publish new articles.

[…] In one ambush incident, the Boers (Afrikaner colonies of the South African Republic) tried to derail Churchill’s train by placing rocks on the tracks. Sharpshooters waited to ambush the survivors, but Churchill took command, and amidst bullets, walked among the survivors to tell them to, “keep cool, men.” […]